Vital and Viable

by the Rev. Dr. Michael Kinnamon, President of the National Council of Churches of Christ

Address to the Synod of the Moravian Church, Northern Province June 14, 2002

First things first: I love the Moravian Church (for reasons that I hope will become clear), and I celebrate the ministry that God has done through you for nearly five hundred and fifty years. That is more than ten times the number of years I have been alive, and my teenage daughters assure me that I am very old. I’m also thankful for the witness to the gospel made by my brother in Christ, Burke Johnson (who is even older than I am), and it is a pleasure to say a public word of appreciation at the start of Burke’s last Synod as president of the PEC. One more word of thanks: I am grateful for the invitation to deliver this message, and pray that God will speak to you through it.

I begin with an understatement: Churches don’t always find it easy to name their own sins! At the inauguration of the Churches Uniting in Christ (to which Gary [Harke] referred in his gracious introduction), each of the covenanting churches was asked to name its distinctive sin that had contributed to the division of the church. The general minister and president of my communion, the Disciples of Christ, said something like this: “We, Disciples, have been guilty of individualism–which, of course, is often a good thing”! So I repeat: Churches don’t always find it easy to name their particular sins.

But sometimes it is also hard for churches to name their particular gifts of the Spirit. I think that may be the case these days for Moravians; and, if so, perhaps a non-Moravian who loves the Moravian Church can be of help. Thus, in the first part of this address, I want to tell you what I see as the gifts you bring to the whole body of Christ, the gifts you hold, as it were, on behalf of the wider church–but I’m going to come at this indirectly, so please stay with me.

Some of you may be familiar with a wonderful little book by the Presbyterian scholar, Shirley Guthrie, entitled Diversity in Faith, Unity in Christ. Isn’t that a good Moravian title? And the book is also organized in a very Moravian way in that Guthrie identifies tensions or competing streams within American Protestant churches by grouping them according to four well-known hymns.

Doctrinal clarity is secondary to lives of embodied faithfulness.

The first group he calls “Faith of our Fathers (and Mothers)” Christians–for whom being Christian is essentially a matter of right belief. In one sense, this isn’t very Moravian since you, like the Disciples of Christ, affirm that doctrinal clarity is secondary to lives of embodied faithfulness. But Moravians obviously do affirm the living tradition of the church. We don’t invent the faith in each generation; we inherit it, passing along the faith we have received.

Many of these “Faith of our Fathers and Mothers” Christians are involved in ecumenical dialogue because they recognize that differences of belief have frequently split the church. Others, of course, are convinced that they have the true faith and are going to hold onto it in splendid isolation.

Being Christian isn’t essentially a matter of believing certain things but of living a certain way, a way marked by active concern for the neighbor.

The second group Guthrie puts under the heading “They’ll Know We are Christians by our Love” Christians. (This song isn’t in your Book of Worship, but I suspect that most of you are familiar with it). For this group, being Christian isn’t essentially a matter of believing certain things but of living a certain way, a way marked by active concern for the neighbor. This second group, if my students are any indication, tends to think that the first group is too dogmatic, too hung up on matters of the head. Meanwhile, the first group thinks the second doesn’t understand the power of sin which binds us, undermining our attempts to love our neighbor. That’s why, they say, we need a savior, not just a moral teacher.

The third hymn Guthrie uses is in your Book of Worship: “Rise Up, O Saints of God.” It is not enough, from the perspective of this group, to believe the right things, or as individuals, to live better, more loving lives. Being Christian is essentially a commitment to that vision, that reality, of justice and peace in human community that Jesus called the Kingdom of God. From the perspective of the first group, this group runs the risk of turning Christianity into a social- political movement. Meanwhile, the third group thinks that the first is too preoccupied with the church and not enough with the world.

This tension was captured for me in a memorandum I received from a colleague during the years I worked for the World Council of Churches. The Faith and Order Commission, which I served as staff, had just returned from Lima, Peru where we had put the final touches on the document Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry–a text, written by Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant theologians from around the world, that expresses basic agreement on these topics. I was feeling pretty good, at which point I received the memo that read: “Congratulations. But how you guys can spend all that time, energy, and money nitpicking your way toward unity on the sacraments when there is starvation in Africa and war in the Middle East is beyond me. All the best. Allan.”

Can you guess Guthrie’s fourth group? “Amazing Grace” Christians. For them, being Christian is not essentially a matter of correct belief or neighbor love or social action, but of personal salvation through experience of God’s amazing grace. Christians are those who have been confronted with the good news, confessed Christ as Lord, and been, in some real sense, born anew. I will leave it to you to imagine what some of the others say about this group–and vice versa.

Now, if you find yourself saying, “These things aren’t either-or” that may be, in part, because you are Moravians! In an either-or era, Moravians (at least in my experience) have been a both-and people. Both evangelical and ecumenical. Both focused on service in the world and focused on intense fellowship in the community of faith. And this refusal to divide what surely belongs together is a gift of the Spirit, a witness of great importance to the church universal.

In an “either-or” era, Moravians have been a “both-and” people.

Let me be more specific. You have affirmed that the church is a servant community in imitation of a servant Lord–and your history bears this out, beginning more than two hundred fifty years ago with your mission to the poor and enslaved in the Caribbean. But you have, at the same time, affirmed that the church is a fellowship gathered around the cross, marked by an evangelical piety that shows forth the “near presence” of our Savior.

You have affirmed that the church is found in local communities of people who treat each other literally as family. But you have, at the same time, affirmed that the church is a global community, a global family, that embraces cultures as diverse as Tanzania and Alaska. A lot of churches say that, but few live it out as clearly and intentionally as you.

Your particular identity, from the days of Zinzendorf on, has been ecumenical.

You have affirmed your distinctive heritage as Moravians, but always coupled with a commitment to the unity of Christ’s one body–which, in the words of the “Covenant for Christian Living,” is laid on you as a charge, as a matter of gospel obedience. That is to say, your particular identity, from the days of Zinzendorf on, has been ecumenical. I tell my students that I am out to change their grammar–that names like “Presbyterian” and “Methodist” are wonderful adjectives but idolatrous nouns, because the noun that defines us is “Christian.” If I’m not mistaken, you understand yourselves to be Moravian Christians, which allows you to learn from other Christians and rejoice together in the gifts which God has given to neighbors of other denominations. Running throughout “The Ground of the Unity” is a spirit that I will call “bold humility”–bold in your proclamation that Jesus Christ is Lord of all creation, but humble in your recognition that you don’t have exclusive rights to him, that your task is to witness rather than to judge.

Names like “Presbyterian” and “Methodist” are wonderful adjectives but idolatrous nouns, because the noun that defines us is “Christian.”

Am I at all on target? Maybe you take all of this for granted; but, if so, you shouldn’t! A both-and people in an either-or era, not because you waffle but because you are focused on Christ whose grace is deeper and wider than we can ever imagine or express.

So, that’s my testimony as an outsider. You have a great deal to celebrate–which is to say, you have lots of reasons to give thanks to the living God.

But, of course, the Moravian Church is also a human community. And many of you, it seems to me, come to this Synod feeling that the church is all-too-human. The “Reality Statement” from last year’s Provincial Elders’ Conference, included in your materials, speaks of being at a crossroads, of being concerned for the vitality, the very viability, of the Moravian fellowship, of being divided by the same contemporary issues that split the wider church. We all know that we should be focused on mission, but it is easy to get wrapped up in internal controversies. We all know that we should trust joyfully in Christ, but it is hard not to be anxious about the future of this community.

In the face of these concerns, I have no great wisdom to offer–but scripture does. And, therefore, my preparation for today has been prayerful discernment of what biblical texts might speak to you at this moment. And the text I kept coming back to is the one now appearing on the screen, Paul’s astonishing words from the beginning of Romans 15.

May the God of steadfastness and encouragement grant you to live in harmony with one another, in accordance with Christ Jesus, so that together you may with one voice glorify the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. Welcome one another, therefore, just as Christ has welcomed you, for the glory of God.

Please think with me for a few minutes about this passage.

The division in Rome, to use Paul’s language, was between the “weak” and the “strong.” The strong were those who believed that there was no need to maintain Jewish dietary laws or observe the special days on the Jewish calendar now that the Messiah has come. The weak (you can bet they didn’t choose the labels!) were those who regarded strict observance of Jewish law as an integral part of their response of faith to Jesus Christ. I have heard ministers dismiss this as a debate over matters that weren’t terribly important, but don’t believe it. As far as the antagonists were concerned, nothing less was a stake than the very definition of what it means to be Christian.

Now, it is quite clear that these two groups were not welcoming one another. (That’s my second understatement of the day.) From chapter 14 verse 3: “Those who eat [those who feel free to eat all foods] must not despise those who abstain, and those who abstain must not pass judgment on those who eat…”–an indication that this is exactly what was going on.

Some things never change, do they? Despising and judging have been characteristic of the church for two millennia. Those who think themselves free from the law look down their noses at those joyless, backward conservatives who hold fast to it. Those who see the law as crucial wag their fingers at those undisciplined, worldly liberals who violate it. Any of this sound familiar?

The apostle will have none of this for two reasons:

• First, no matter what you may think of these others in the church, God had already welcomed them! “Welcome one another, just as Christ has welcomed you….” All of us have been accepted by grace alone. Eating or not eating meat will not make you acceptable.

• Indeed, no behavior can make you righteous, for you are saved (reconciled to God) only by God’s grace.

Second, these attitudes of judging and despising set us up, to use Paul’s language, as “lords” of each other, whereas the point is that we are now Christ’s people and he is lord.

Chapter 14:4: “Who are you to pass judgment on servants of another? It is before their own lord that they stand or fall.” The Greek word translated “servant” (οἰκέτις, oiketis) actually means “member of the household.” Paul is emphasizing not the subordination of followers to Christ but the distinctive place of honor that each of us has through him.

To use our freedom from the requirements of the law without regard for the consequences this has on our sisters and brothers is to abuse that very freedom.

In Romans 15:1-7, Paul clearly identifies himself with the strong group. As he writes in Galatians, “Christ has set us free.” But, and here is the catch, there is a commensurate responsibility to use our freedom in ways that build up the community. To use our freedom from the requirements of the law without regard for the consequences this has on our sisters and brothers is to abuse that very freedom.

As Paul says in these verses, the norm for all Christian action is Christ–the One who, though strong, became weak for our sake. The One who, though truly free, became a servant for our sake. The One who, though equal to God, became flesh for our sake. Self-limitation for the sake of others–that is the guideline for those who claim Christ’s name.

Can you see the implications of this for life in the contemporary church? Ours is an age when we celebrate that the church is diverse; but we still have great trouble living with its diversity. The New Testament scholar, Robert Jewett, suggests that Paul’s words in Romans 14 and 15 offer three guidelines for living with genuine difference.

Protect the integrity of those with whom you disagree.

First, protect the integrity of those with whom you disagree. Many of you, writes Paul, believe (as he did) that nothing is unclean in itself, and therefore, feel free to eat anything. But, he continues in 14:23, those who have doubts about this are condemned if they eat because they would not be acting from faith. That is, they would be violating their own consciences. Do not, says Paul, force your brother or sister into such a position, especially if they are doing what they do in an attempt to honor God. Verse 13 sums it up: Resolve never to put a stumbling block in the way of your neighbor.

Behind all of this is a profound understanding not only of the gospel but of human nature. What we so often seek in others is a reflection of ourselves. This, however, is not love as Paul understands it. Saint Augustine captured it perfectly when he wrote that love (ἀγάπη, agape) means “I want you to be.” The other, who may see the world so differently from you, is a child of God for whom Christ died. If you sarcastically dismiss the conservatism of some church members, stop it! If you sarcastically dismiss the liberalism of some church members, stop it! Protect the integrity of those with whom you disagree.

Protect your own integrity.

Second, protect your own integrity, or as he puts it in chapter 14, “Be fully convinced in your own minds.” I could no more regard scripture as inerrant than I could fly. It would be a massive violation of my own integrity to deny what, as I see it, are the undeniable results of historical scholarship. But no matter what I think, scripture is inerrant authority for those who treat it that way. They should not claim that I do not take the Bible as authoritative, because that isn’t true. And I should not force them to see it through my lens, as if that were even possible.

The third guideline is really the key: Encourage growth in one another. Chapter 14:19: “Let us then pursue what makes for peace and for mutual upbuilding.” This is why what Jewett calls Paul’s “strenuous tolerance” is not the same as putting “all welcome” signs on the door.

Encourage growth in one another.

Paul is talking about an active welcoming that seeks to learn from others, from those who are different, so that the body may be built up. The world talks about “getting along” for the sake of civic harmony. The church talks about communion for the sake of mutual growth–precisely because all of us see the mystery of God in a mirror dimly and, therefore, need each other, especially when we disagree.

Paul doesn’t call for agreement, nor does he call for compromise. Rather, he insists that it is precisely our willingness to live trustfully with acknowledged differences that bears witness to the God whose grace alone holds us together. It is not that Paul thinks that both arguments have equal merit. He identifies with the strong group and makes that case vigorously throughout his letters. Here in Romans 15, however, he insists that the unity of the body is more important that political victories because it is that unity which witnesses more powerfully than anything else to God’s including, reconciling grace.

Paul doesn’t call for agreement, nor does he call for compromise. Rather, he insists that it is precisely our willingness to live trustfully with acknowledged differences that bears witness to the God whose grace alone holds us together.

To put it another way, the demand for conformity undermines the very nature of the church. Just as Christ’s welcome does not wait for the transformation of the sinner but comes as an unconditional gift, so the competing factions in Rome were to accept each other without demanding conformity. And, here’s the punch line, such community is an embodiment of the gospel itself. Mutual welcome is God’s intent for all creation, and we are to be the sign, the embodiment, of it here and now.

I must admit (before I move on to the brief final part of my message) that there are times when Paul sounds much more exclusive than he does in Romans 14 and 15. This happens, it seems to me, whenever he feels that the gospel of God’s unconditional, inclusive grace is being distorted. Paul’s most contentious letter is probably Galatians where he wishes, at one point, that his opponents would castrate themselves One thing this tells us is that Paul didn’t always practice what he preached–but there is also a deeper issue.

In Galatians, Paul’s opponents apparently taught that obligation leads to freedom–be circumcised, keep the law, believe the right things and you will be saved. And Paul has to say No! you have it precisely backwards. Freedom leads to obligation. You are free! You are accepted! You are welcomed! Now live as those whose lives are marked by the welcome you have been extended in Christ. “Welcome one another, just as Christ has welcomed you, for the glory of God.” This is the gospel that defines us. If we get this straight, then we can live with other differences in the community. The insistence that others become like us undermines the gospel, which is that all of us are saved by grace and grace alone. I think that is what Moravians learned on August 13, 1727.

It is possible, of course, to be open to others because you don’t believe much of anything. Live and let live. But for Paul, openness to others stems precisely from the nature of Christian faith. Those who have been set free from the fear that they are unwelcomed gain the freedom to welcome others. Those who know themselves loved unconditionally find the strength to grow in a community of genuine disagreement.

“Welcome one another, just as Christ has welcomed you, for the glory of God.” God is not glorified by our victories over each other. God is not glorified when the church looks like a like-minded club. God is glorified by our welcome of each other.

I hope these reflections on Paul’s theology of Christian community have been helpful. Perhaps they can set a framework for the discussions you will have with one another during these days together.

I want to use my final seven minutes by returning to the questions raised by the PEC’s “Reality Statement.” Is the Moravian Church, Northern Province, vital? Well, who knows?

That depends on the extent to which your life as a community is centered on and grounded in Christ. Vitality means energy, purpose, and whenever we sense these things, it is not our vitality we celebrate, but God’s vitalizing spirit for which we give thanks.

The PEC also posed a second question: Is the Moravian Church in this part of the world viable? Do you, in other words, have the critical mass to make a difference? Again, who knows? The Bible is filled with images of leaven and mustard seeds and multiplied loaves and fishes. We bear witness with what we have and leave the results to God.

It is, however, appropriate to ask: How can a community our size best use our resources to participate in God’s mission? And in response to that question, I have three brief recommendations.

First, in order to live out your “charge” to promote unity among Christians, I urge you to become participants in Churches Uniting in Christ (CUIC). CUIC is a substantive covenant through which nine U.S. Protestant churches have made a number of promises to one another before God, including a promise to share the Lord’s Supper with “intentional regularity,” to work together more fully in mission (especially locally), and to engage in intensive dialogue toward a fully reconciled ministry. The churches retain their historic identity as Presbyterian Christian or Methodist Christian or Episcopal Christian or Disciples Christian, but they pledge themselves to live more closely in sacred things: sacraments, mission, ministry, faith.

One great advantage of CUIC for the Moravian Church, given your limited personnel, is that it would link you with nine other churches without requiring nine separate dialogues, nine sets of relationships. Even more importantly, CUIC includes three African American Methodist churches, and, thus, tears away at the color barrier that has so distorted Christianity in this culture–something which I know is of great importance to Moravians.

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (with whom you are in full communion) recently joined the original nine churches as a “partner in mission and dialogue”–a category that allows them to get their feet wet before possibly diving in. Perhaps that would make sense for you as well. I know that Burke is prepared to speak more about this later in the Synod.

Second, I also recommend that the Moravian Church help all of U.S. Christianity focus much needed attention on Africa. Once again, it makes sense, given limited personnel, to concentrate your energy on certain mission priorities, and your deep involvement in Tanzania puts you in a perfect position to help the rest of us acknowledge the plight of African sisters and brothers.

Your deep involvement in Tanzania puts you in a perfect position to help the rest of us acknowledge the plight of African sisters and brothers.

You know the situation. With an annual per capita income of $280, Tanzania is the seventh poorest nation in the world. Servicing its $7.5 billion foreign debt takes up 40% of the government’s annual budget, leaving little for health and education–which is why life expectancy is now less than fifty years and the literacy rate has fallen from 90% in 1990 to 68% in 2000. Forty-three percent of children under five are malnourished to the point of stunted growth.

We need to say it loudly and directly: This is simply outrageous, intolerable! Debt relief and open markets are no longer options to be debated and implemented piece meal; they must happen now, coupled with increased assistance. The church’s voice should be ever louder in the public debate over foreign policy toward Africa–and you can lead us.

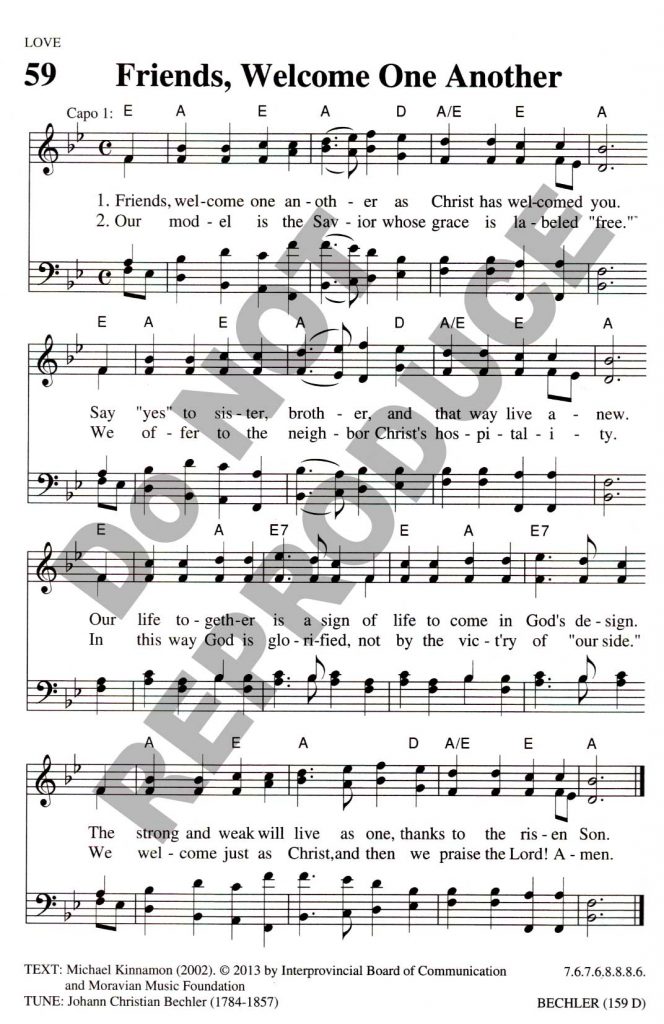

My third recommendation goes back to the words of the apostle Paul. I hope you will affirm in this Synod that your life as an intimate community of faith, the way you live with one another, is itself a witness to the living God whose purpose is shalom for all creation. I am going to conclude, in the only appropriate way for such a gathering, by offering this message of Romans 15:7 in the form of a hymn. This will quickly prove why I’m a theologian and not a hymn writer, but please accept this as my tribute to a church I love.

The tune of “Jesus Makes My Heart Rejoice” was too hard, so imagine the words now appearing on the screen to the tune of “Sing Hallelujah, Praise the Lord.”

Friends, welcome one another as Christ has welcomed you.

Say “yes” to sister, brother and that way live anew.

Our life together is a sign of life to come in God’s design.

The strong and the weak will live as one, thanks to the risen Son.

Our model is the Savior whose grace is labeled “free.”

We offer to the neighbor Christ’s hospitality.

In this way God is glorified, not by the vict’ry of “our side.”

We welcome just as Christ and then we praise the Lord. Amen.

A reproduction of this hymn set to music is included below.

The Rev. Dr. Michael Kinnamon was President of the National Council of Churches of Christ when this address was delivered. A pastor in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), and is also a professor at Eden Theological Seminary in St. Louis, MO.

This hymn is included in Sing to the Lord A New Song, which can be purchased HERE. Hymn (C) 2013 by Interprovincial Board of Communication and Moravian Music Foundation. All rights reserved.