Learning Curve: My Journey of Understanding LGBTQ+ Issues

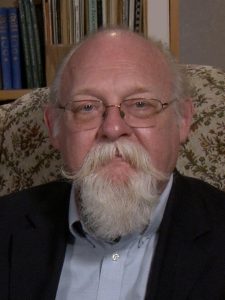

The Rev. John Jackman

Somewhere around junior high school, I became aware that there was such a thing as homosexuality. My teenage reaction was “eeeww.” I just didn’t get it. I liked girls, I couldn’t comprehend why a guy would look at another guy that way. I honestly can’t remember any time in those teenage years where I thought that might be a fun thing to do, or had any temptation in that direction.

But that’s because I am 100% heterosexual. Claiming any credit for that would be like self-righteously giving up candy corn for Lent (I hate candy corn). I remember a woman once saying, “Why are men so interested in breasts? I just don’t get it.” Like her, I don’t get it — from the other side. But that doesn’t mean I can’t understand and empathize with the experiences of folks who are different from me, and who experience the world differently.

Practically every church had at least one person who people suspected might be “queer,” but mostly we all pretended not to notice.

Back then, homosexuality wasn’t such a big, hot-button issue in the church, even the evangelical church. Most gay folks were totally closeted. Practically every church had at least one person who people suspected might be “queer,” but mostly we all pretended not to notice. After all, he’s a good tenor (or organist, or whatever); she volunteers on the flower committee or the annual fundraiser.

As a young man, I worked for a while with a lady who most people assumed was lesbian. She lived 20 minutes out of town, was extremely private about any personal life, would often talk about “we went to the movies” or “we had a good trip” – but would never tell anyone who the other part of the “we” was. That was pretty much how it was in those days. I figured it was her business, and didn’t pry. It didn’t bother me, either.

One of the things that pastoral candidates must do prior to ordination is Clinical Pastoral Education. It’s a bit similar to internship for doctors. You serve as a chaplain at a hospital or some other institution with a group of other candidates. A supervisor will push you to reflect personally and theologically on your experiences. Most of the time, this is at a general hospital, but I had the good (though challenging) fortune to do CPE at Allentown State Hospital in Allentown, PA – one of the old-style state mental hospitals that are now mostly closed. This was no “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” it was a really well-run hospital with a staff of dedicated professionals.

My assignment was to act as chaplain for one long-term women’s ward and for the men’s short-term ward. This latter was the psych unit where people without insurance would go while in serious crisis, usually staying a couple of weeks. One of the things that we saw a lot of were teens or young adults who were gay and had actually tried to kill themselves, or were obsessed with the idea. Caught between their inner self and the rigid expectations of family and the outside world, some of them saw suicide as the only way out. Nearly a third of LGBTQ+ between 18 and 25 have attempted suicide. I remember one young man who said, “Why would anyone choose this? I would give anything to be normal.” Most reported always having felt they were different, even before puberty and teenage hormones. Out of all the conversations I’ve had with gay folks over the years, I never felt like a single one of them had made a choice – just as I never made a conscious choice to be straight. One thing I will tell you – sitting and listening to the heart-wrenching story of a young man whose family and church has rejected him, and now sees suicide as the only solution leaves a mark on your soul.

Sitting and listening to the heart-wrenching story of a young man whose family and church has rejected him, and now sees suicide as the only solution leaves a mark on your soul.

I knew a number of gay folks who struggled with other issues as well – alcoholism and drug abuse, self-mutilation, depression, childhood sex abuse – just like straight folks. Sometimes they would come to me to talk about those issues, and then we wound up talking about the issue of being gay in a straight world. I often wondered how much the strain of pretending to be straight – or defying church, family, and society – contributed to those other issues. I did observe that the worst internal conflicts happened for those who were trying to deny their sexual orientation; this often resulted in a personal or psychiatric crisis. And I saw that when a gay person was able to come out (at least to themselves), and accept themselves for who they were, the depression, drug abuse, and other problems could also then resolve. Living a lie is never healthy – spiritually or emotionally.

Every church I have been pastor of has had gay members and gay folks in the extended families of members. One congregation included an individual who was intersex – a person who had been born with both sets of “equipment.” This happens much more often than anyone talks about. Back in the 1960’s, the decision would be made to surgically “fix” the baby the easiest way – usually to make them female. Today those decisions are made with parents based on genetic and other testing rather than just ease of surgery. This particular person was quite open about the issue, most are not. But in considering the issues around intersex births, I also began to consider how LGBTQ+ issues might be similar. The improvement in brain scanning and genetic testing in recent decades have revealed different brain development in gay or trans folks than occurs in straight people. Birth order appears to be a factor, too. Repeated and extensive studies have demonstrated that the probability of a boy growing up to be gay increases for each older brother born to the same mother. Each older brother increased the probability of being gay by about 33%, a rather startling statistic.

In 1985, I got an interesting request – to come as a guest preacher at the Metropolitan Community Church in Lancaster, PA. If you’re not familiar with the MCC, it is a Christian denomination specifically for LGBTQ+ folks. I agreed, and we scheduled a Sunday afternoon when I was free – they were meeting in rented space in the fellowship hall of a Presbyterian church. Now, at this time, though I was comfortable with LGBTQ+ folks and had counseled many, I was still personally uncomfortable with some of the issues. I briefly considered if in the sermon, I should address the issues of whether or not homosexual behavior was sinful in and of itself. I prayed about it quite seriously, and I felt that I got an answer: “NO.” I felt led to talk instead about Christ’s love and how we follow Him and grow in faith. That’s what I did, and I had a very positive experience. They had a potluck supper after the service, and asked me to stay; several individuals asked if they could talk to me privately. I had a good conversation with each of them about their spiritual journey, and their honesty about their spiritual struggles was refreshing.

I felt led to talk instead about Christ’s love and how we follow Him and grow in faith.

I was smart enough not to tell anyone at the Moravian church I was serving about this guest preaching event; one of my predecessors there had come out as gay during his ministry, left his family and the church. I don’t judge him; those were hard times for closeted gay folks; but the experience left a lot of wounds that were still fresh, and I’m sure there would have been a bad reaction. I suspect that I may be the only straight Moravian pastor who preached at an MCC back in those days.

In 1991, after doing some work in Nicaragua, I had an interesting experience in Honduras. When I got off the plane, my friend Sam Gray asked if I was up to doing a wedding while I was there. It seems there was a couple who had been legally married for years, but had joined the church and wanted to now have a Christian ceremony. Sam was not ordained at that point, and it seemed like every time an ordained pastor came through, something got in the way so this dear couple could not get married. Of course, I agreed. I learned that in Honduras, as in a lot of other countries, legal marriage and church marriage are completely separate things – “divorced” as it were. You go to the court to get legally married – and then, if you are a Christian, you go to church and have the religious ceremony. They are entirely separate. Very different from the US, where religious marriage and legal marriage are tightly intertwined. On the plane back to Miami, my mind was grinding on this idea. I was thinking of a number of gay folks I knew who were Christian, were living together, and desperately wanted to be married. I thought that was the solution. The civil ceremony and the religious ceremonies should be separate. Gay people should have the right to be legally married, and have the full protection of the law – and then each denomination could wrestle on its own about whether to allow religious marriage. At this time, I was still very uncomfortable with church weddings for same-sex couples – but I felt strongly that they had the right to be married in the eyes of the law. After all, in our country, there is supposed to be separation of church and state – and the religious arguments should not apply to civil ceremonies.

I had another eye-opening experience a few years later. During a period when I was mostly doing film production and wrote for one of the major national video magazines, I worked with a woman named Kim Reed. While most of our relationship was virtual (emailing articles, talking on the phone), I got to know her pretty well – we produced a couple of videos together, we did workshops together for conferences and conventions – some at big deal events like the National Association of Broadcasters. I was flabbergasted one day to learn from someone else that Kim was trans. The astonishment was that I had no idea at all – I had known some other trans people before this, but it had been pretty obvious. Not so with her, she was a perfect textbook example of how well such a transition can be done. It didn’t change our professional relationship at all – though we were able to have a few personal conversations about her story. She documented her story well in an award-winning film, Prodigal Sons – worth watching, it was featured on Oprah. She later went on to produce Dark Money, a film on how secret political donations have changed the state of Montana after the Citizens United ruling. Also worth watching. But one lesson that I learned from Kim is that I don’t know everything!

Over the years, quite a few people have sat down with me as a pastor to tell me how they view this issue. Rarely does anyone ask me what I believe – or what I think the Bible says! Part of what a pastor does is listen with an open heart. One storyline that has occurred again and again is that of a person who either had a fleeting same-sex encounter as a teen, or was tempted to have one. Especially in my generation, a lot of them decided that they would do the “right” thing and resist the same-sex temptation, pursuing only heterosexual relationships. A lot of them went on to assume that this was the experience everybody has – hence the strongly held, common idea that sexuality is simply a choice that everyone makes somewhere along the way. But that’s a misunderstanding. One psychologist pointed out to me that these folks, by definition, are bisexual. And bisexual people do have a choice, especially if they believe in being monogamous. It’s the same choice heterosexuals have when they marry – to love only one, “forsaking all others.” But they don’t actually seem to have a choice about whether or not they are bisexual. While universalizing from one’s personal experience is natural, it’s mistaken and confusing. Most people don’t choose one way or the other – they either are straight or they are gay – no choice involved. But a certain part of the populace (those who are bisexual) do have a choice which gender they will pursue.

It didn’t take long for me to be convinced most of the verses have nothing at all to do with sexual orientation as we understand it today.

After our 2014 Synod, I volunteered to be a table moderator for the discussions on homosexuality. In the process of preparing for that, I was challenged several times with the question of whether same-sex marriage in the church could be justified from a Biblical perspective. At that point, I was still on the fence. Of course I was familiar with the passages that seem to mention homosexuality, but since we rarely preach on them, I hadn’t really taken the time to do a full-blown study: looking carefully at the Greek and Hebrew, reading scholarly articles, and researching the historical practices of the time that the writers had in mind. By the way, most church people would be shocked about the common sexual practices of Greece and Rome in the first century – the practices that Paul was actually talking about.

It didn’t take long for me to be convinced most of the verses have nothing at all to do with sexual orientation as we understand it today. Like so many other issues in Christian history, the prevailing culture had read what they wanted into a few cherry-picked verses, often with very little understanding of the first century culture that Paul and others were actually referencing. I encourage everyone to do some in-depth reading on the issues: translation problems of 1 Corinthians 6:9-11 and 1 Timothy 1:9-10; reading Romans 1 in the context of Romans 2; and understanding the Holiness Code of Leviticus. Then I reviewed how the current beliefs about “Biblical marriage” came about (mostly not from the Bible), and I concluded that I probably could, in good conscience, officiate at a legal same-sex wedding. This doesn’t mean that I will officiate at any wedding that comes along; and doesn’t mean I think that every pastor should agree with me – it’s where I ended up. Others may be at very different points of this journey, and may have had different conclusions. That’s fine – we can respect one another and recognize that were are serving God together, perhaps in slightly different ways.

I’m really glad of this opportunity to review my own spiritual journey on this topic; I’ve never reflected on it in quite this way, and certainly have never set it down for others to read. I hope that you can respect my journey, even if you are one who has ended up with different conclusions than I arrived at.

The Rev. John Jackman is a Moravian pastor, author, and filmmaker. He is currently pastor of Trinity Moravian Church in Winston-Salem, NC. He lives out in the woods in Lewisville with his wife Debbie, daughter Abby, two cats, and six ducks.

Featured photo © Mariaam. Courtesy of Dreamstock.